|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bio |

Art |

Fantasy |

Covers |

Munchausen |

Stuff |

Us |

Pyle |

Tomorrows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bio |

Art |

Fantasy |

Covers |

Munchausen |

Stuff |

Us |

Pyle |

Tomorrows |

|

|

The Project

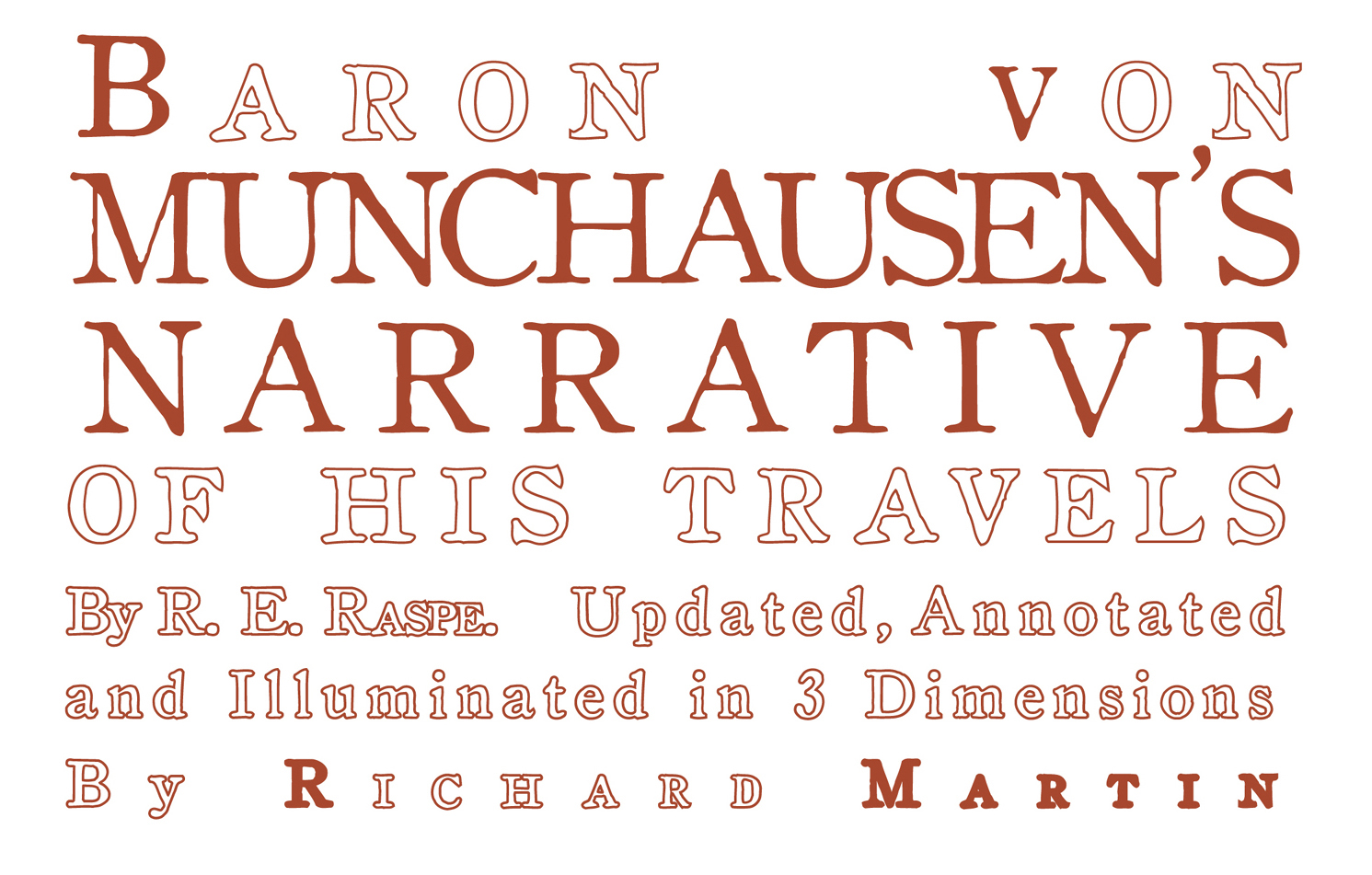

Richard Martin's thesis research for his MFA in Graphic Design concerned the history, development and application of 3-dimensional viewing systems. This was the logical development from his dual interest in art and stereoscopy. His thesis project was a prototype book, its design and art wholly integrated with the narrative. The visual experience of the book’s design is enhanced through the conversion of his two-dimensional illustrations into three-dimensional imagery, using three different digital programs. Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of His Travels, by R. E. Raspe, is an internationally known classic in the public domain. Originally published in 1785, the book has been altered, adapted and re-arranged since its inception. The core of the book - the humorous and fantastic elements of the narrative and the costume/swashbuckling characteristics of its protagonist - is perfectly suited to Mr. Martin's artistic interests and style. Mr. Martin has designed the template and structure of the book and adapted, annotated and added to the narrative. Just recently, Disney and Pixar have announced that all of their new animated films will be released in 3D; where once there were die cut and folded foamcore displays, theater lobbies now showcase lenticular one sheets. Baseball and film tie-in "bubblegum" collector cards now have lenticular 3D and motion. Mr. Martin believes there is a tremendous future in the publishing, production and graphic design industries for the creation of 3D lenticular art for advertising, promotional and editorial use. He is currently seeking a publisher for the project.  A Brief History of 3D Viewing Systems

Representational painting is always an illusion; the illusion of three dimensions on a two-dimensional surface. The French term, "trompe l’oeil" – fool the eye – dates from around 1800, though illusory murals date back centuries earlier (Hollman 6). Stereoscopy – the root, stereo, is from the Greek for "solid" – was developed sometime around 1832, prior to the invention of photography (Pellerin 43). Stereoscopy is a type of "trompe le cheveau" – fool the brain – that combines two two-dimensional pictures to form one "three-dimensional" image when viewed through the stereoscope. The English physicist Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875) is credited with the invention of stereoscopy. His paper, On Various-Hitherto Unobserved-Phenomena of Binocular Vision, was presented to the Royal Society of London in June of 1838. It concerned itself with geometric figures and asserted that an artist would be able to draw the two component images necessary to fuse in the stereoscope and produce a three-dimensional image.  In 1891 the French inventor Louis Ducos du Hauron (1837-1920) obtained a patent for "stereoscopic images that produce their effect in daylight without the use of the stereoscope". He called the process the "anaglyph", and it involved the superimposition of stereo pairs in red and blue and the use of red and blue filters for viewing. Unlike stereoscopy, the process made it possible to increase the size of the 3D image as desired (Pellerin 121).  While the anaglyph process enabled the use of projected (still) images, the comfort of use of the red and blue glasses was a major detriment. It wasn’t until 1936, with Edwin Land’s invention of the Polaroid filter, that three-dimensional movies became practical. In the Polaroid process, two movie cameras mounted about 6 inches apart are used to simulate the interocular. Two films are shot simultaneously. One camera is equipped with a vertically oriented polarized lens, the other with a horizontal. When projected synchronously on a single screen, the images looks to the naked eye like an out-of-focus picture. When viewed through a pair of Polaroid glasses, with both vertically and horizontally oriented lenses, objects leap off the screen (Wensberg 53).  Line screen systems are a group of direct vision three-dimensional techniques that do not need a special viewing device such as anaglyphic or Polaroid glasses. As with stereoscopy and anaglyphs, line screen 3D is based on each eye seeing a differentiated image corresponding to binocular parallax. A composite image is created taking a typical stereoscopic pair and interlacing it into alternate vertical strips. A screen made of alternating opaque and transparent strips of the same width is placed in front of this image so that the strips from the first image are seen by the left eye and those from the second image are seen by the right eye. The brain combines the two views and reconstructs a three-dimensional image (Frizot 153).  The Illustrations

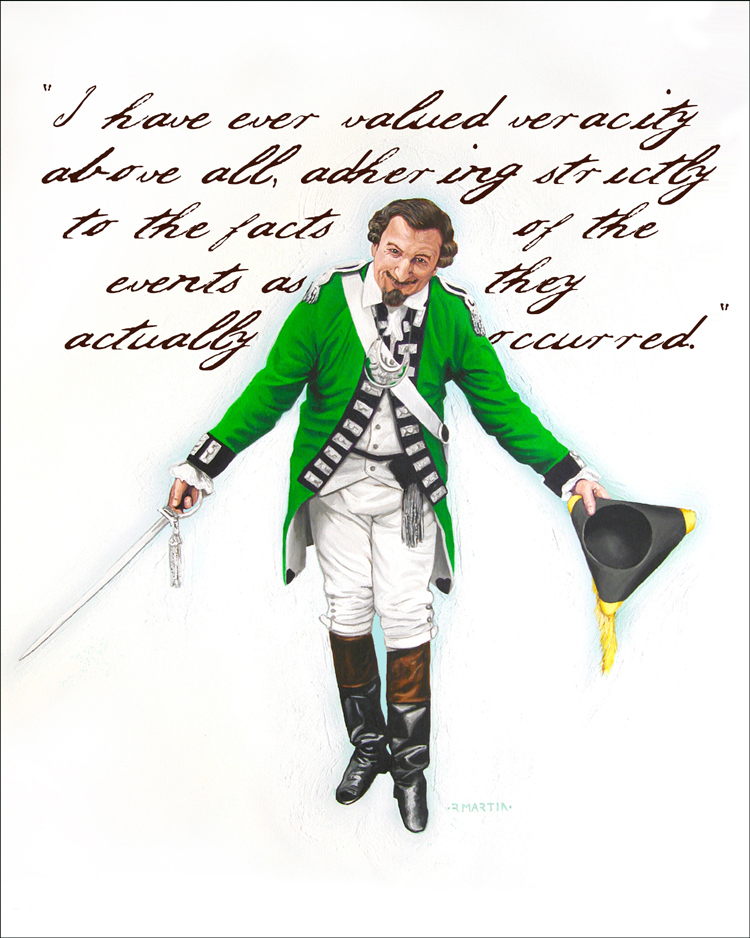

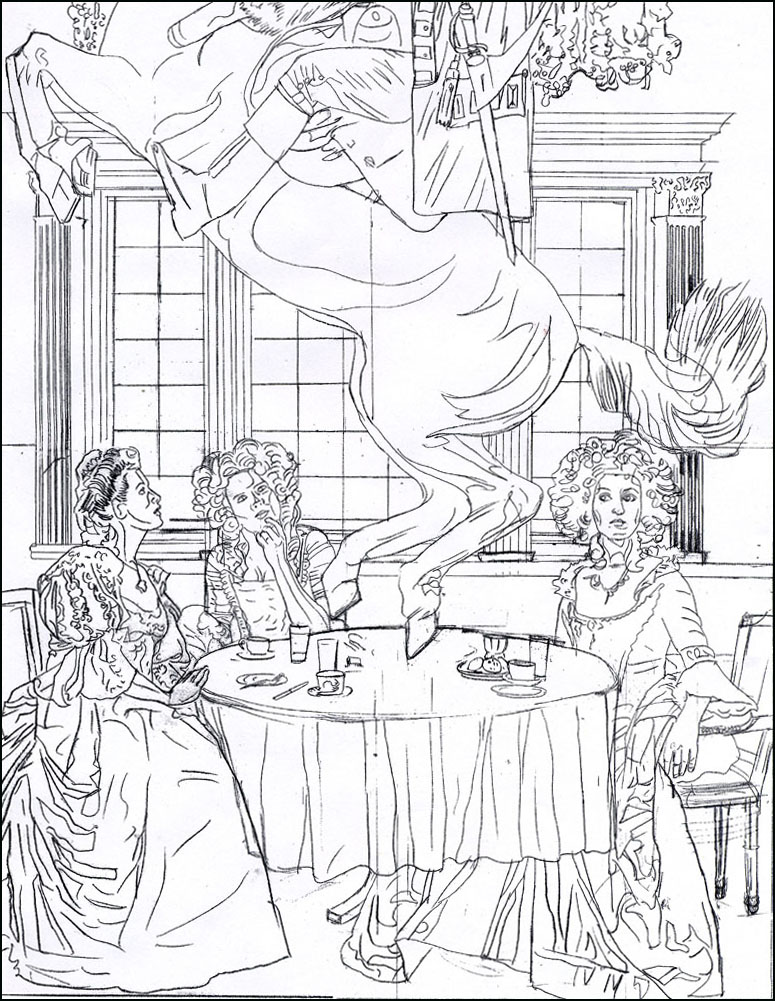

Munchausen’s Narrative is illustrated with seventeen full page 3D illustrations by Mr. Martin. Rendered in paint on canvas, they have been digitally scanned, separated and interlaced to create the illusion of depth. All of the illustrations were created using traditional means. The initial concept for the art is put down as a thumbnail, and a list is made as to what elements are needed to create the scene.  The image of the Baron is based on illustrations by Gustave Dore. Much like the John Tenniel Alice illustrations, this has become the prevalent view of the Baron’s features. Once all of the visual elements have been collected, an 18 by 22 inch drawing is created and transferred to canvas.

As with all of Mr. Martin's work, the painting is done in acrylic polymer paints. White sable brushes, an airbrush for some of the backgrounds, and the occasional palette knife are used to apply the paint to the ground.  In order to create the 3D conversions Mr. Martin used a combination of three software programs: Adobe PhotoShop (to separate the 2D art into layered components), Home Illusion (a depth painting program) and PowerIllusion (an interlacing program). The latter two programs were created by Wahn Raymer and Ben Johnson of Lawrenceville, Georgia. The image below is a montage of "GL window" views that represent the layer distortions when the depth maps have been linked to the image:  Images created from layered objects in a PhotoShop file are used to generate the multiple parallax views necessary for the lenticular process. These images are then precisely divided among all the lenses through a process called interlacing, so that each original image has a raster of image data sequentially placed under each lens. PowerIllusion is especially designed for this process; it can precisely calibrate the interlacing to match the pitch of the lens screen and the technical specifications of the printer. By using these multiple digital processes the illustrations are converted into lenticular images. What we call "true 3D" are images with figures that have a dimensional "wax museum figure" look. A 3D image can be created with two-dimensional art that creates images with figures that are separated by space but have the look of flat cutouts on a multi-plane camera. Mr. Martin's goal is to take his paintings and convert them to the more voluminous "true 3D" appearance. As can be seen above, the visual representation of the enforced dimensionality is more akin to a bas-relief than a freestanding sculpture. Nonetheless, in the 2D, "3D" lenticular, the eye is fooled into seeing more volume.  The Pages

Besides creating the narrative art for the book, Mr. Martin chose fonts and colors, designed the template and structure of the book and adapted, annotated and added to the narrative. What follows is a sample chapter, detailing (and explaining) one of the more famous events in "a life filled with incident and wonder"...     References Carswell, John, ed., The Singular Adventures of

Baron Munchausen, By Rudolph Raspe and Others, New York, Heritage Press, 1952 Curtain, Dennis P., "Lenticular Prints", How Do I Do That?, 3 March 2007, how/lenticular/lenticular> Frizot, Michel, "Lenticular Screen Systems and Maurice Bonnet’s Process", Paris in 3D, eds., Reynaud, Francoise, Catherine Tambrun and Kim Timby, Paris, Paris Musees, 2000 ---, "Line Screen Systems", Paris in 3D, eds., Reynaud, Francoise, Catherine Tambrun and Kim Timby, Paris, Paris Musees, 2000 Hollmann, Eckhard, and Jurgen Tesch, A Trick of the Eye: Trompe l’Oeil Masterpieces, Munich, Prestel, 2004 "Lenticular Imaging Process", Lenticular Plastic Company of Europe, 14 March 2007, http://lpc-europe. com/lenticular_process Pellerin, Denis, "The Anaglyph, a New Form of Stereoscopy", Paris in 3D, eds., Reynaud, Francoise, Catherine Tambrun and Kim Timby, Paris, Paris Musees, 2000 ---, "The Origins and Development of Stereoscopy", Paris in 3D, eds., Reynaud, Francoise, Catherine Tambrun and Kim Timby, Paris, Paris Musees, 2000 Raymer, Wahn and Ben Johnson, Home Illusion Manual, Lawrenceville, GA, Home Illusion, 2005 Wensberg, Peter C., Land’s Polaroid: A Company and The Man Who Invented It, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1987 | Return Home | Artist's Bio | Stamp Art | SF Fantasy | Other Covers | Baron Munchausen | Kid Stuff | Contact Us | Howard Pyle | Yesterday's Tomorrows | |

||